Estimated reading time: 12 minutes

Recently, a thread was posted on Twitter by a former Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) staff member describing a phenomenon they claim to have observed time and time again during their years working in the organization. This phenomenon, which they call the “Danger Zone,” is described as affecting several DSA chapters nationwide irrespective of size, activity, or ideological leaning. They describe the “Danger Zone” as a state that arises from a lack of external-facing work around which a chapter can focus its efforts. According to this DSA intellectual, this causes the organization to focus on internal work — structure building, amending internal documents, and refining political positions. This results, our source warns us, in unnecessary personal conflict, ideological infighting, grievances, and an inward focus of a chapters’ members, driving away “comrades” and neglecting less active members. When an organization enters the “Danger Zone,” it supposedly begins to suffer from ineffective work, splits and unnecessary arguments, and a struggle against allies instead of the enemy capitalist system. The solution, according to this former staff member, is to always have external-facing work to engage in to prevent stagnation and falling into the trap of the “Danger Zone.” We must “organize in order to grow and build power,” which does not, we are once again reminded, come in the form of struggle, amendments, or resolutions.

Normally, it wouldn’t be worthwhile engaging with discourse on Twitter, but because of the overwhelming positive response to the thread, including affirmations of its relevance to all organizations, not just DSA chapters, it is evident that this is a product of a widespread and troubling attitude among organizers in the U.S.

Now, there are some truths and some merits buried in this argument, if we can only excavate them from the worship of spontaneity that pervades it. What this person is attempting to describe is the concept of stagnation, which is very real. An organization is a machine; it is a vehicle. If it is not moving, if it is not progressing, it is failing to serve its purpose — not only that, it is beginning to degrade. That which is not growing and coming into being is already beginning to fade away. As Marxists, as Communists, as members and leaders of Communist organizations, we must always be engaged in the process of building revolution. We must take care to ensure our organizations are always moving toward this end and always furthering this goal.

Stagnation is a lack of qualitative movement or direction, and is characterized by wasted effort and wasted time. It is often the death knell of organizations, leading to burnout, despair, and nihilism. Stagnation is, in essence, the opposite of progress, a perpetual holding pattern whereby we are all just waiting for something to happen.

Stagnation does not necessarily mean failure. Failure, when it is part of the process of trial and error, is actually progressive. When we make mistakes, we learn. When we learn from our shortcomings and failures, we develop. Development is part of progress, and when we develop we are engaged in the process of building. As long as we are learning, we are growing. That is also not to say that we do not expect moments of calm when we are assiduously performing the plan we set out and agreed upon. Every moment is not necessarily a heightening of the struggle, and all organizations must make numerous strategic and tactical retreats, withdrawals, and breaks. None of these things are bad in and of themselves. (After all, we are Marxists — nothing has any positive or negative quality in itself, but derives those qualities from how it relates to the project).

Stagnation can also appear in the form of circular movement, where completed actions and programs leave you right where you started with no qualitative advancement. In cases like these, success does not always constitute progress. If an action is performed, regardless of how “successful” it was, if there is no real outcome, no lessons learned, no structures built, you have not really moved from where you were. In fact, a “successful” action can disorganize your organization and demobilize your cadre if the tactical or strategic direction is incorrect. Think, for instance, of making a push to elect a certain local politician in the hopes that they will open a breathing window for socialist discourse in your region. Once the election is over, many of the structures that were built to mobilize voters, because they were highly specialized (over-specialized), collapse. When this politician instantly turns coat and betrays the socialist values they claimed to espouse, you may lose morale and membership. This “success” was actually a failure.

When we make a mistake and learn from it, it was worth that time and effort. If we refuse to learn from it and continue to repeat the same mistakes, it is not and we have stagnated. We have failed to make progress towards our goal. This is the danger of stagnation, and it is a danger we must do our best to avoid.

This former staff member identifies one way to avoid stagnation, which is to find a direction and move in it. Programs and projects, with defined goals and practical milestones, are essential to construction and progress. An organization must have a direction around which to focus its efforts. If a vehicle has all of its wheels pulling in different directions, it does not move, but when all of its wheels are united and moving in the same direction, it makes forward progress, motion. So it is with organizations. Without a direction, there is no motion; there is no motivation, there is no unity.

Where our friend’s argument fails is that it lacks an understanding of progress, construction, and priority. Their “Danger Zone” doesn’t actually give an adequate definition of stagnation. We can restate this in a clear way as the answers to the following series of questions:

What exactly is the “Danger Zone” that this person describes?

DSA chapters fall into the “Danger Zone” when they focus on internal work instead of external work. It is in these moments, they say, that ideological differences among members become clear, issues between members erupt into conflict, and less active members are neglected and grow distant from the organization.

Is the “Danger Zone” actually stagnation?

No. In fact, if the “Danger Zone” makes existing contradictions between members clear and ideological struggle comes to the forefront, it is not actually dangerous at all! Debate, struggle, working through contradictions with your comrades; these are essential elements of development. This is how correct positions are adopted and direction and unity clarified.

This person effectively makes a distinction between internal and external work, arguing that external work is the only progress possible. However, internal development, building structure, clarifying ideology and political position is organizing. It is progress.

If this is the case, why is the “Danger Zone” so destructive to DSA chapters?

It is necessary to resolve or reconcile contradictions between members, because their resolution is motion. However, there are some contradictions that are irreconcilable. A dogmatic anti-Communist liberal who refuses to engage with Marxism in good faith cannot be reached through struggle because you cannot establish unity with them. The nature of DSA being a big-tent organization, which allows anyone to obtain membership and makes no central structural attempts to develop them, means that people like this can become members of the organization. They can, and do, amass significant influence and take up positions of leadership. Therefore, when the organization attempts to take up internal work, which involves ideological and political struggle, it is destructive instead of constructive.

It is clear that this is the result of a massive structural failure endemic to the DSA as a whole. It is a product of petit bourgeois liberalism which can put forward no scientific analysis and instead defaults to liberal conceptions of democracy and individualism. They have no internal structure upon which to develop their various chapters. Some chapters develop their own education programs, but without standardization they are variable in scope and effect. As a result, members do not engage in adequate political development. Additionally, a lack of a central protocol for “grievances,” or criticism, causes struggle between members to quickly devolve into destructive pettiness and personal conflict.

Why is focusing solely on external work not actually a solution?

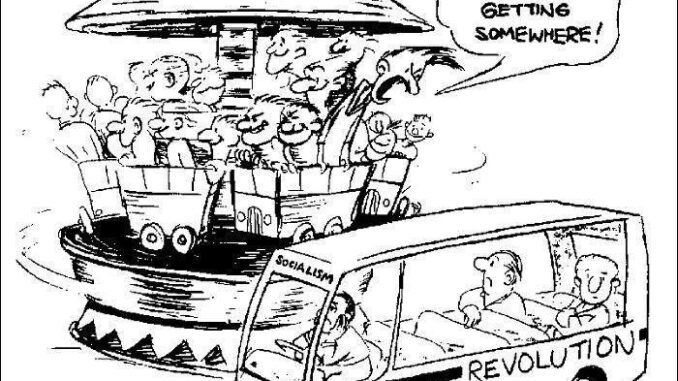

Imagine a merry-go-round. If you pick a point on the outside edge, it appears to be moving very fast. If you pick a point closer to the center, it is moving much slower. If you pick a point in the center, it is not moving at all.

External work only gives us the appearance of movement if it is not also paired with internal work. When we engage in canvassing, tabling, holding protests, even engaging in aid work, it makes us feel as if we are progressing. We are, after all, “getting out there.” We are putting boots on the ground, we are talking to our neighbors and community members. We say we are “organizing” them.

But mobilization is not the same as organizing. If you get a thousand people to come to a march, but then they go home afterwards and never come out again, what progress have you made? What have you built? If you pile a hundred people on a merry-go-round, where are they traveling to? Nowhere. In fact, they are not really moving at all.

As such, it is entirely possible to be thoroughly engaged in external work AND ALSO be stagnated in your development. In fact, focusing solely on external work obfuscates stagnation and lack of development, making one feel as if they are organizing when they are not.

The U.S. left, and DSA in particular, is obsessed with action, with what we call spontaneity. All of DSA’s major efforts have been organized around spontaneous events in American politics; falling in behind Bernie Sanders and M4A and the “Fight For 15,” all of these things are products of spontaneous populist demands.

In many ways, organizing is the antithesis of spontaneity. Organizing is deliberate, it is planned, it is paced, it is controlled and directed. It is the work that happens behind the scenes when the streets clear of protestors and everyone else goes home. Organizing prepares us to take advantage of spontaneity, because moments of spontaneous passion and rebellion from the people are times of consciousness raising and opportunities for qualitative leaps in growth. It is the structures built between spontaneous moments that allows that momentum to be taken hold of.

For someone who lacks a holistic, scientific view, external work appears to be the preferable, or indeed, the only, form of motion. They see a person running on a treadmill and shout, “My, how fast they’re going!” But if the building is on fire, who is making more progress, the person sprinting on the treadmill or the person walking towards the door?

Is this not the real “Danger Zone”?

We must reframe our understanding of what actually constitutes organizing. We must refocus our efforts from circular, wasted time and effort towards actual development and construction. We cannot use external work as an excuse to avoid the hard work of ideological struggle and commitment. We cannot use it to ignore contradictions and shortcomings in our structures and among our membership, pushed down like repressed emotions. Those contradictions must be dealt with or they will erupt.

At this time, our movement has no political formation capable of realizing class power and fighting for the interests of the working classes. Therefore, while external work is important, internal work, organization building, is primary. We cannot shy away from it as something dangerous or scary or incorrect, we must embrace it and engage with it wholeheartedly. Comrades, the “Danger Zone” is not actually dangerous at all. It is necessary work that must be done if we are to make forward progress towards our goals. If we avoid it, we fall into stagnation, regression, and irrelevancy. If we refuse to engage with it, if we refuse to engage in learning and development, then our failures truly are failures and our efforts are in vain.