Estimated reading time: 14 minutes

The U.S. Supreme Court has declared Indigenous tribal sovereignty in the U.S. Empire a mere legal fiction. The case of Haaland v. Brackeen was putatively about a federal law, which the Court upheld by a 7-2 majority, but in reality, this panel of unelected judges unanimously affirmed that the United States Federal Government has both the power and the right to violate the sovereignty of Indigenous nations.

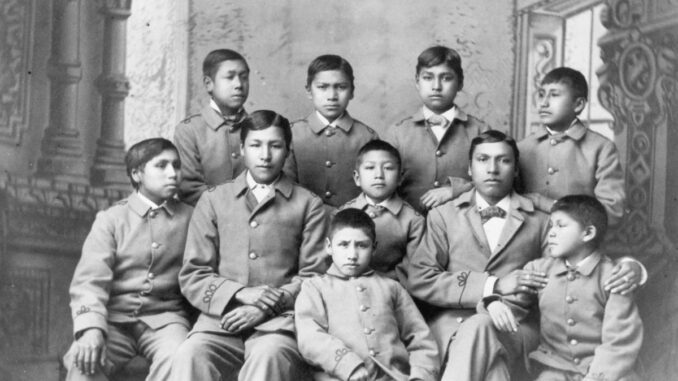

Since its conception in the first English colonies, the U.S. colonialist project has been a genocidal assault on the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. Through the combined force of arms, biological agents, ecological devastation, starvation, kidnapping Indigenous children, and land theft — all propped up by the ideological force of a colonialist legal system — United States has stolen 99% of the land historically held by the Indigenous nations. Land is the basis of all economic organization as the most essential and basic building block of production; it is, as Marx said, “the universal subject of human labor,” and the original source of all wealth. By stealing land,the U.S. Empire has liquidated the economic basis of pre-colonial Indigenous ways of life and forms of social organization. The treaty territories were reduced to little more than government grants, administered under the thumb of the Bureau for Indian Affairs. Existing property relations were forcibly dissolved, and replaced with a system of private property and enclosure, transplanted from England; conquered peoples were removed from their lands and forcibly converted into classes of smallholders, while the ruling families of a few “civilized tribes” joined the ranks of the slaveholding planters in the U.S. South. “Adoption” — the kidnapping of Indigenous children by white settlers, against the wishes of the child’s parents, community, and nation — has proved an effective weapon in genocides around the world, and has long been a staple of the U.S. colonialist regime. The U.S. Empire has never lost its originally genocidal character, and the legal theft of Indigenous children by settlers carried on until 1978, when Indigenous nations gained legal protections against kidnapping with the passage of the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA).

The Act, as the Supreme Court recognizes, “aims to keep Indian children connected to Indian families.” Under the ICWA, an “Indian child” is a child who is a “member of an Indian tribe” or who is “eligible for membership in an Indian tribe and is the biological child of a member of an Indian tribe.” If this child lives on a reservation, the ICWA grants the tribal courts exclusive jurisdiction over custody proceedings. If a state court adjudicates custody, the ICWA controls and overrides local state law. The parent or custodian and the tribe have the right to intervene in any custody proceedings, to request extra time to prepare for those proceedings, to examine all reports and documents, and for court-appointed counsel.

The ICWA gives the tribe the right “to intervene at any point” and to challenge the state court’s decree. The ICWA also codifies custody placement preferences for Indigenous children: “(1) a member of the child’s extended family; (2) other members of the Indian child’s tribe; or (3) other Indian families.” State courts are required to follow these preferences.

The case of Haaland v. Brackeen began when three white families, joined and sponsored by the fascist-captured State of Texas, challenged the ICWA, alleging that it infringes on their constitutional rights. Their grounds were as follows: First, that Congress never had the authority to pass the ICWA in the first place, rendering the law invalid. Second, that the ICWA violates anti-commandeering principles in the Tenth Amendment (essentially, that the law transforms state governments into servants of the Congress, conscripting those governments to spend their own money to enforce federal decrees). Third, that a provision in the Act allowing individual tribes to alter how it applies to them violates the non-delegation doctrine, the legal rule that Congress cannot pass off its law-making power to other groups, agencies, or organizations. Most importantly, fourth, that the ICWA uses “racial classifications that unlawfully hinder non-Indian families from fostering or adopting Indian children.” The plaintiffs unashamedly argued that the Indian Child Welfare Act is racist, because it protects Indigenous children from white kidnappers.

The challenge is the court case Haaland v. Brackeen. Deb Haaland, Secretary of the Interior, brought the appeal to the Supreme Court after the 10th Circuit decided in favor of Chad Brackeen and the other parties who seek to steal Indigenous children from their communities and nations. The 10th Circuit court held that the ICWA violated the Equal Protection clause — that, in essence, white would-be kidnappers had suffered racial discrimination.

On June 15, 2023, the Supreme Court upheld the ICWA by a vote of 7-2. Chief justice Alito and justice Thomas, infamous for standing out as extreme-right fascists even among a far-right Supreme Court, stacked with recent Trump appointees, are the two dissenters. Although the majority upheld the ICWA, they did so on the narrowest possible grounds while laying out the legal justification for the law to be challenged in the future. They clearly and unequivocally restate the principle, often expounded by the U.S. imperial government, that Indian sovereignty has ended.

How does the court justify the ICWA? The far-right justice Barrett, a Trump appointee, wrote the majority’s decision. She states that “Congress’ power in this field is muscular, superseding both tribal and state authority,” and that “[V]irtually all authority over Indian commerce and Indian tribes lies with the Federal Government.” Then, when discussing the treaty clause of the U.S. constitution, she off-handedly remarks that “[u]ntil the late 19th century, relations between the Federal Government and the Indian tribes were governed largely by treaties.” Now, however, she argues that Congress can legislate Indian affairs based on what she euphemistically calls its “trust relationship” with the Indigenous nations — the paternalistic, white saviorist, nonsensical position that, by subjugating this continent’s Indigenous people through centuries of brutality that have scarcely been paralleled in history, the “Federal Government has charged itself with moral obligations of the highest responsibility and trust toward Indian tribes.”

Barrett thus handily does away with the major arguments of Brackeen and his fellow litigants, but only with a sweeping restatement of Congressional authority. Yes, says Barret, Congress does have this power, because Congress possesses plenary and ultimate authority to govern Indian affairs. The civil rights of Indigenous families, children, communities, and nations are “safe” from encroachment by the states and by white private citizens — but only because the Indigenous nations are under the watchful eye of their shepherd, the U.S. Federal Government. In the instance of the ICWA, Congress was kind and benevolent; should Congress determine it wishes to be less generous — that it wishes, for example, to extinguish all remaining reservations and duties to the Indian nations — it could just as easily do that.

Most importantly, the seven justices held that the Supreme Court actually can’t decide on the Equal Protection claim brought by Brackeen. This is the bomb buried in Haaland. The left-fascist Democrats and their allies long ago established that the equal protection clause of the U.S. constitution applies to the oppressors as well as to the oppressed, in essence, enshrining the idea of “reverse racism,” or “misandry.” Any government agency that “discriminates” against white men can be found in violation of the equal protection clause. Smirking lawyers remind us that the constitution protects us all equally, not all equitably. The equal protection issue raised (but not reached) in Haaland is the claim that the ICWA disfavors white parents. This issue wasn’t decided because the case was procedurally improper for deciding it. The court could have run roughshod over the posture, but it would have been too bold a move, too openly flaunted the political nature of the court, which of course postures itself as “above” politics while engaging in fundamentally nothing else.

In an obscure bit of lawcraft, Barrett states, “Article III requires the plaintiff to show that she has suffered an injury in fact that is ‘fairly traceable to the defendant’s allegedly unlawful conduct and likely to be redressed by the requested relief.’ Neither the individual petitioners nor Texas can pass this test.” The Court declined to make a ruling simply because Brackeen and his fellow petitioners brought their case in the wrong court — a legal technicality. Barrett doesn’t reach the question of whether they were right at all. Why? Because the Supreme Court cannot order the state courts and agencies, which were not brought as parties to the suit, to do anything about the enforcement of the ICWA. In a footnote, Barret archly remarks that “[o]f course, the individual petitioners can challenge ICWA’s constitutionality in state court.” She is signaling that the state courts of Texas can and should bounce this issue back up to the Supreme Court for a proper adjudication — this time, in Brackeen’s favor.

Nor can we afford to lose sight of the fact that the liberal justices didn’t write any of their own concurrences to articulate alternate grounds for the decision. Although they compose an absolute minority of the court, concurrences nevertheless allow judges who sit on the weaker side of the court to stake out positions they can defend, both to the other justices who might be persuaded to adopt their arguments, and, perhaps more importantly, to the public (especially in this instance when the court’s legitimacy has been repeatedly brought into question by the highly public war between the two wings of the ruling class). But the liberals on the court — Kagan, Sotomayor, and Jackson — didn’t write anything. They joined in the decision written by Barrett, endorsing the majority’s view that the Indian nations are the child-like wards of the Federal Government and that, should the U.S. Congress so decide, treaty rights and tribal sovereignty can be dissolved at any time.

Surprisingly, the far-right reactionary justice Gorsuch wrote a concurring opinion, in which he details the historical injustices dealt by the U.S. Empire to the Indigenous nations of North America. He writes, “[I]n those early decades, [the 1850s–1860s] schooling [to assimilate Indigenous children] was generally not compulsory” but that “[t]he federal government had darker designs.”

By the late 1870s, its goals turned toward destroying tribal identity and assimilating Indians into broader society. Achieving these goals, officials reasoned, required the “complete isolation of the Indian child from his savage antecedents.” And because “the warm reciprocal affection existing between parents and children” was “among the strongest characteristics of the Indian nature,” officials set out to eliminate it by dissolving Indian families. …

Certain States saw in this shift an opportunity. They could “save… money” by “promoting the adoption of Indian children by private families.”

This restarted a now-familiar nightmare for Indian families. The same assimilationist rhetoric previously invoked by the federal government persisted…. “If you want to solve the Indian problem, you can do it in one generation,” one official put it.

Despite this acknowledgement, Gorsuch, too, argues that the federal government has ended its treaty-making period with the Indian nations. However, in contrast to Barrett, he puts it this way: the sovereignty of the Indian nations “creates a hydraulic relationship between federal and tribal authority. The more the former expands, the more the latter shrinks” but “the only restriction on the power of the Tribes in respect to their internal affairs arises when their actions conflict with the Constitution or the laws of the United States.” Sotomayor and Jackson joined in this portion of Gorsuch’s concurrence, creating a three-justice minority who still nominally recognize tribal sovereignty — at least, for now. None of the justices, however, would bat an eye should Congress unilaterally abolish this legal fiction.

This is in sharp contrast to the majority and to both the dissent written by Thomas and that by chief justice Alito. Thomas’ dissent is filled with vile, white supremacist logic, laying bare the actual underpinnings of the legal regime: “For today’s purposes, I will assume that some tribes still enjoy the same sort of pre-existing sovereignty and autonomy as tribes at the Founding,” he muses, indicating of course that no contemporary Indigenous nation has retained real sovereignty, that all are under the federal government’s thumb, and that “tribal sovereignty” is a legal fiction. More than that, Thomas argues the familiar refrain of the genocidaire that the genocide is already mostly complete; that the remaining Indigenous tribes are merely “remnants of tribes that [have] been absorbed” by the individual states and assimilated into the colonizing population; that there are no “real Indians” left to defend their rights and sovereignty and to fight for their liberation. Thomas ends his dissent with a damning statement, one that outlines the limits of the Haaland decision: “[T]he majority holds only that Texas has failed to demonstrate that ICWA is unconstitutional.” In other words, what remains of tribal sovereignty in the U.S. Empire is still in the fascist Supreme Court’s crosshairs — and everyone knows it.

It is the extremely brief concurrence of the reactionary Kavanaugh that encapsulates the fundamentals of the majority’s decision, displaying, as Thomas does, the danger and the purpose: “I write separately to emphasize that the Court today does not address or decide the equal protection issue.” They are begging for a chance to hear the case again, but properly plead, and properly situated. The fascists intend to strike down what remains of the sovereignty of the Indian nations — the right-wing fascists openly, and the left-wing fascists by quiet assent. The fascists want every opportunity to bring to completion the anti-Indigenous decisions issued by their less brazenly reactionary predecessors, before the Supreme Court’s recent extreme-right capture during the Trump presidency.

It is, perhaps, in recognition that the great masses of the U.S. working class no longer sees the Supreme Court as some defender of the downtrodden, that there is now, in the political and public discourse, a powerful undercurrent that correctly identifies the court as an illegitimate, anti-democratic institution that serves to protect the ruling class. The court expresses capitalist class-power, nothing more. For true, people’s democracy to rule, the reactionary power of the court must be destroyed. For the colonially oppressed peoples to achieve liberation, on the basis of real sovereignty, the Supreme Court, and the whole existing U.S. Constitutional order, must be abolished.