Estimated reading time: 44 minutes

152 years ago, the city of Paris threw off the shackles of the reactionary government of France and repudiated the conservative political order. The radical Blanquists, Jacobins, and Proudhonists of Paris, the great masses of proletarians and artisans of the City of Light, rejected the hypocritical peace of Adolphe Thiers and the so-called Government of National Defense. In its final, doomed hours, swamped by the myriad hundred thousands of the Versailles government armies, manning the failing barricades and retreating step by step into the heart of the European city of revolutions, the Communards held out their desperate last stand draped in the red flag of socialism. When the rattle of the bullets stilled, the last two hundred Communards lay dead before the wall of the Cimetière du Père-Lachaise. Although the Commune had been destroyed, its lessons would live forever.

The 18th Brumaire of Louis-Napoléon

Our story begins with the fall of the July Monarchy, itself the result of a brief explosion of street fighting in the early 19th century which rid France of the last restored Bourbon king, Charles X. King Louis-Phillipe d’Orléans took the place of Charles and instituted a vaguely liberal constitutional monarchy.

In February of 1848 — the year that saw Europe explode in upheaval against the so-called Metternich system, with revolutions breaking out in Italy, Vienna, Budapest, and Berlin — the people of Paris demanded Louis-Phillipe liberalize his government. When he failed to meet their demands, revolution swept the streets of the city. The radical socialists of Paris and the bourgeois liberals joined together to erect barricades in the heart of the city. Louis-Phillipe, unwilling to give the order for the army to fire upon the people of France and fearing the republican revolution would send him to the same fate as his father and uncle — regicide — fled first Paris and then France. The bourgeois ministers who reaped the rewards of this revolution would have no such compunction about ordering the army to turn their guns on their former allies, the radical socialists. The July Monarchy came crashing down.

The 1840s were also the years of the great potato blight that swept through Europe. Financial turmoil and an enormous market crash played a decisive role in spurring the 1848 revolutions and, in France, left millions starving and without work.

The bourgeois liberals at once moved to cut out the radical socialists and utopians from the new government. They founded what the French call the Second Republic (following the First Republic, that of the Revolutionary Government in 1792). Although the bourgeois government that took over from Louis-Phillipe promised to enact the “right to work” laws sought by the socialists, instead, they purposefully constructed mismanaged National Workshops in Paris to provide make-work for those thrown into unemployment by the blight, the financial crash, and the tumult of the February Revolution.

When the bourgeois republic of 1848 closed the National Workshops, as poorly managed as they were, the workers in Paris exploded in outrage. Thousands had come from the surrounding countryside to seek work, and now they were told they had scant days to clear out of the city. On 23 June 1848, the city rose. Barricades were built across the heart of Paris and the armed citizenry demanded the establishment not only of a democratic republic, but a social republic: one that solved the crisis of poverty and property. The Second Republic responded by calling out the National Guard, that body of petit-bourgeois shop owners formed into a 40,000-man-strong Parisian militia. Under General Cavaignac, the National Guard crushed the revolt of the June Days, shuttered the workshops, and deported nearly 4,000 insurgents to newly conquered French Algeria.

Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, nephew to the former emperor of France and self-styled Prince, was permitted by the Second Republic to return to his native soil and to run in the parliamentary elections of 1848. In September of that year, he won a seat in the new National Assembly. Catholics and peasants, who missed life under the Empire which had at least seen to their needs, overwhelmingly supported Prince Louis-Napoléon; he was seated in the Assembly to cries of “Vive Napoléon!” and, more troublingly, “Vive l’Empereur!”

In December of 1848, Louis-Napoléon won the newly-created presidency in a landslide 74% vote in the first French election with universal male suffrage. The memory of the glories won by the emperor Napoléon had not faded. The France of the restored and then the July Monarchy was a beaten France, hemmed all around by former enemies that still cowered at the thought of the revolutionary wars that Paris and her armies had brought (along with fire, requisition, and the sword) to all of Europe for a generation. Embittered former soldiers of the emperor and those who longed for the days when tribute flowed into France — instead of out of it — swept the victorious miniature second Napoloéon to power. This movement was backed not only by the old officer corps and the class of career military men created by Napoléon I, but also by the big bourgeoisie, the mighty capitalists of France.

In December of 1851, facing the end of his term limits and unable to convince the Party of Order and the French Parliament to lift them, Louis-Napoléon followed his more famous predecessor. He staged a coup.

A fanatically loyal army was all he needed. On the morning of 2 December, Louis-Napoléon deployed troops all over Paris. His opponents were arrested. On the walls of the city were plastered flyers proclaiming the Six Decrees:

In the name of the French People. The PRESIDENT of the Republic DECREES: The national assembly is dissolved. Universal suffrage is re-established. The French people are convened in their committees. A state of siege is declared. The council of state is dissolved. The ministry of the interior is charged with the execution of the present decrees.

On January 14, 1852, the Prince-President declared himself Emperor. The Second Republic was abolished and the Second Empire begun. From 1852 until 1870, the social revolution, which had broken out in 1848 and been suppressed by petit-bourgeois republicans who had, in turn, been crushed by bourgeois monarchists, was crushed under the weight of the Second Empire. Napoléon III went so far as to restructure the face of Paris. Under his direction, the Baron Haussmann tore down entire districts, plowed broad avenues through the old warren of streets, and made certain no one could barricade the center of Paris — just as they had during the fall of the July Monarchy or the June Days, again.

The Franco-Prussian War

In 1870, Germany was being unified by iron and blood under the ungentle guidance of the arch-conservative Prussian minister, Otto von Bismarck. Von Bismarck had, in his own way, helped to shackle the social revolution in Prussia by granting constitutional reforms to disarm Prussian political radicals, just as Louis-Napoléon had argued for universal suffrage merely so he could have himself voted emperor.

When Leopold of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, a prince of Prussia, seemed poised to take the throne of Spain, France took action to prevent an encirclement on both borders. Although the prince’s candidacy was withdrawn, Otto von Bismarck published a doctored telegram, called the Ems Dispatch, that appeared to show a diplomatic slight between the King of Prussia and a French ambassador. Napoléon III declared war. Many in his court approved, as did the big landowners and bourgeoisie in France, hoping to restore the French Empire to its former glory. Military advisors and Napoléon III himself believed that the southern German states would ally against Prussia to help serve as a check on their aggressive northern neighbor.

The French army left Paris on July 28, 1870, driving for the German city of Metz. Far from joining the French, the southern German states revealed secret treaties of aid to Prussia, freeing up the entire Prussian army, renowned for its bloodthirstiness and precision, to concentrate against France. After a brief campaign, Napoléon III, surrounded at the small French border-town of Sedan, surrendered to the Prussian army on September 1, 1870.

Prussia did not accept the surrender as the end of the war. It was Bismarck’s plan to reduce France as a European power; to do so, they would accept only an unconditional surrender. At home, the Second Empire was overthrown when news reached Paris. A group of moderate Republicans, Jules Favre, Léon Gambetta, and General Louis-Jules Trochu, led a coup against Napoléon’s remaining ministries and declared themselves to constitute the Government of National Defense.

The Socialists of Paris

Commune member and National Guard general Antoine Brunel said that the revolution that began on March 18, 1871 was “provoked by patriotic sentiment,” and he was right. For Benoît Malon, member of the Commune and the International Workingman’s Association, the Commune was essentially a socialist undertaking, and he too was right. Gaston Da Costa, a follower of the great revolutionary conspirator Louis-Auguste Blanqui and deputy procurator of the Commune, saw the Commune as a continuation of the Jacobin tradition of the first great French Revolution, and he too was right. The journalist and poet Maxime Vermersch saw in the flames set by the dying Commune a foretaste of the purifying revolution that was still to come, and he also was right. Massenet de Marancour, leader of a National Guard battalion and participant in the Commune’s battles, saw the entire event as the working class falling into a trap set by the bourgeoisie so the latter could have done with any threat to their rule, and he was right as well.

Communards, The story of the Paris Commune of 1871, As told by those who fought for it, Mitchell Abidor Ed., Marxists Internet Archive (2010)

At the time of Napoléon III’s defeat, Paris had many currents of radicalism and socialism within her walls. At the extreme right were the bourgeois republicans who wanted to see the end of the Empire but who demanded protection for private property, safety from the “mob,” and suppression of everyone to their left.

The socialists, of every stripe, advocated for what had come to be known as the “social revolution.” Everywhere in Europe, the questions of the future had been divided, cut in two. There was the “political question” — republic or monarchy — but there was also the “social question” — property or equality. Since the eruption of the French Revolution in 1789, every power in Europe had colluded to prevent the working people from answering the social question. Republicans, monarchists, parliamentarians; all were horrified by the specter then haunting Europe, the specter of Gracchus Babeuf and the sans-culottes of Paris, the specter of Communism.

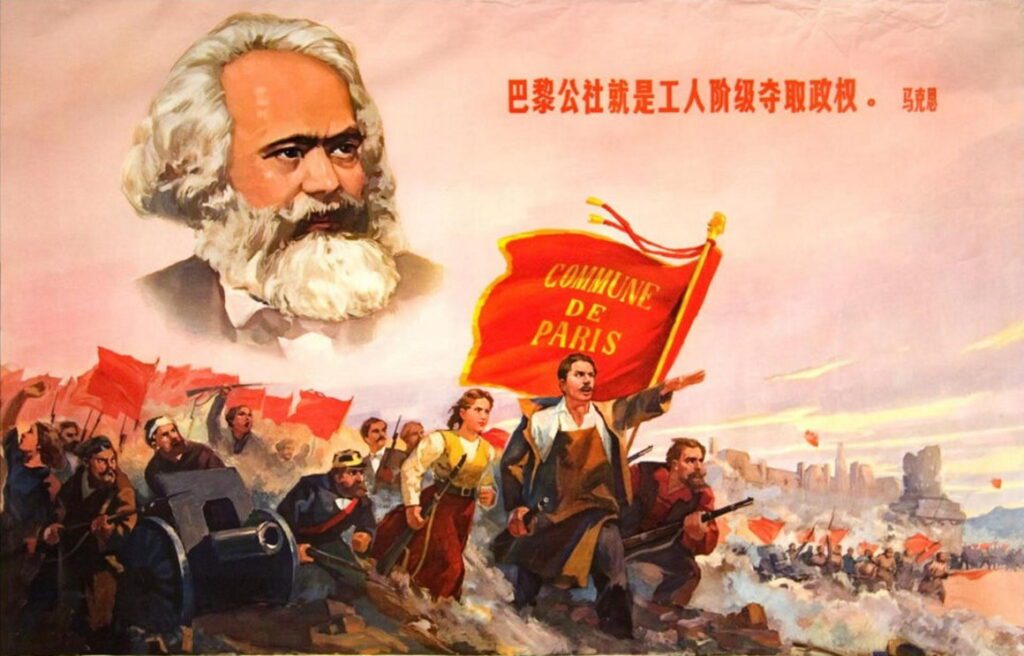

Pierre Joseph Proudhon, although dead by 1865, lived and worked in Paris and left his legacy there. There were many Proudhonists among the Commune. There were also Jacobins and Babeufists, the heirs of Robespierre and Gracchus Babeuf, two towering figures of the French Revolution. Also among these socialists were the followers of Louis Auguste Blanqui. Although Marx called them “pure revolutionists,” for they followed Blanqui’s theories of the conspiratorial overthrow of the capitalist state, most had no social or economic solutions which would follow such an overthrow. Ideologically, most of the socialists within the Commune were unformed — they had no distinct comprehension of how they were to set about achieving socialism — what economic measures they should take. Their ultimate creation, the Commune, serves as the Marxist model for the dictatorship of the proletariat.

The two strongest streams of socialism, then, were the anarchism of Proudhon (which had been criticized thoroughly by Marx) and the vulgar putschism of the Blanquists. Yet, many of the members of the Commune’s governing bodies were also members of the International Workingmen’s Association — the party to which Marx and Engels belonged, and that would be involved in the Haymarket Massacre in 1886.

The average Communard was the average Parisian: young, between twenty-one and forty years of age. They included artisans and craftsmen. They were skilled and semi-skilled workers. Shoemakers, printers, small-scale artisans, construction workers, day laborers, domestic servants, shopkeepers, clerks, and men in the so-called liberal professions. The women of the Commune came from the world of women’s work, the textile and clothing trades, and prostitutes.

Of the 733 people participating in political clubs, 115 were women (15 percent), and 198 held a position within the Commune (27 percent). These were socialists without a precise program, or rather with many programs that had yet to be tested. Adolphe Thiers’ armies would start the fires used to test them; the Commune would finish them.

The Government of National Defense

On the morning of September 4, 1870, all of Paris poured into the Palais Bourbon. Debate was raging within. Jules Favre had proclaimed the end of the empire, and Adolphe Thiers, the most perfect servant of the murderous capitalists, called for the nomination of a provisional government of national defense. The crowd and the partisans, which included both the bourgeois republicans and some radical elements, moved to the Hôtel de Ville. There, they found a gathering of the most prominent socialists and quarante-huitards (Forty-Eighters), veterans of the failed 1848 revolution.

The Prussians wanted not only the official surrender of a government they could trust, but also the transfer of now-occupied Alsace-Lorraine. Louis-Napoléon was sent packing to Great Britain. The partisan Government of National Defense sued for “peace with honor,” but refused to accept a loss of territory. The Prussian army advanced into France and, unopposed, marched all the way to Paris.

This new government was aggressively conservative. They made it clear that they were committed to “God, Family, and Property.” Paris took on a festive air, all its residents confident they would be able to resist the Prussians, just as their ancestors had resisted the Austrians during the first Revolution of 1789. At the same time, the wealthiest residents of Paris fled the city.

The socialists mobilized at the same time. The Arrondissements, the districts of the city of Paris, each created a local “vigilance committee,” composed of coalitions of radicals, which set out to organize the defense of the city. On 15 September, the committees published a red poster demanding elections for the municipal government. They formed a single Central Committee of the Twenty Arrondissements and signed the red poster. They demanded popular control over defense, the food supply, housing, and the universal armament of the Parisians. The word “Commune” was heard on the streets, referring back to the old Insurrectionary Commune of the Revolution. The Prussian armies surrounded Paris and took its forts, even as the Government of National Defense and France’s wealthy capitalists took flight.

The first siege of Paris began on 19 September. The Prussian army ringed the city around, occupied its outlying forts, and encamped in the palace at Versailles. The Parisians treated it lightly until they heard, at the end of October, that the last hope of relief was gone: the French army under siege at Metz inexplicably surrendered to the Prussians. On October 31, this boiled into rage against the Government of National Defense. Angry workers attacked the Hôtel de Ville and, led by Blanquists, stormed it. Militants announced a new government but, once the crowd dispersed, the Government of National Defense swept in and arrested most of the leading socialist partisans.

By December, people were “talking only of what they eat, when they can eat, and what there is to eat…. Hunger begins and famine is on the horizon,” according to the journal of Edmond de Goncourt. Signs were hung advertising “canine and feline butchers.” Calls for the Commune grew louder, and twice more, the Vigilance Committees put up red flyers announcing that the hour had come for Paris to govern herself.

During the siege, the Vigilance Committees did what there was to be done to help distribute the little resources they had. The Government of National Defense suspended rent payments and debt repayments. The National Guard swelled to 400,000 strong and its petit-bourgeois, shopkeeper character was completely overwhelmed by radicals, socialists, and workers who joined either for ideological reasons or because the Guard continued to pay a stipend, even while the city was starving.

On January 28, 1871, the Government of National Defense agreed to the first preliminary armistice with the Prussians, ending the siege of Paris and permitting food to re-enter the capital. Two days later, the government signed the surrender at the Hall of Mirrors in Versailles. France would have to pay an enormous war indemnity and cede the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine to the Prussians. The government scheduled new elections almost immediately, despite the outcry that this would favor monarchists and conservatives. True to the fear, the monarchists dominated the National Assembly, which removed to Bordeaux rather than its ancient seat of Paris. Adolphe Thiers, an avowed restorationist, was elected head of the executive authority of the republic. Thiers and the other reactionary capitalists had been long suspected during the war of favoring a slow strategy of attrition so the Prussians would bleed out the radicals in Paris. Many had heard the wealthy muttering “Better Bismarck than Blanqui.”

Although the armistice had disarmed the remnants of the French armies, the National Guard were permitted to keep their weapons and, above all, their cannons. Some of the guard units had paid for those guns themselves. Thiers and the new government were wary of the National Guard, and feared that they would side with the radicals — which they would, because they had been thoroughly infiltrated.

On March 7, the National Assembly ended the moratorium on debts and rent, declaring repayment due immediately on penalty of eviction from rented rooms. They also ended the daily stipend of 1.50 francs for national guardsmen, leaving tens of thousands of families without enough money to buy food or fuel. Adolphe Thiers and the National Assembly moved the seat of government from Paris to Versailles and issued their orders from the safety of the old royal palace.

On March 17, Thiers decided to be done with his enemies in Paris, the militant socialists and republicans. On 18 March, the Versailles government sent army troops to take the cannons from the National Guard of Paris. The guns had been moved to Montmartre and Belleville, where they could command a range of fire over the city. He said, “Businessmen were going around constantly repeating that the financial operations would never be started until all those wretches were finished off and their cannons taken away. An end had to be put to all this, and then one could get back to business.”

At Montmartre, the 171 cannons were ranked up into two rows on the heights and also on a plateau further down. At 4:30 a.m., March 18, troops began to enter Montmartre. A column of 4,000 men under the command of General Bernard de Susbielle began marching to place Pigalle at the foot of the great hill. As women in these neighborhoods woke to buy bread first thing in the morning, they found themselves facing the French army.

The residents of Montmartre mounted the steeples of their churches and sounded the tocsin bells, which had been the call of the insurrectionary Commune going back to the first Revolution of 1789. The National Guard answered. The civil war had begun.

The Civil War in France

Although the troops from Versailles had arrived to secure the cannon in Montmartre, they had failed to bring horses with them, and so the guns remained immobile. When horses finally came, they started to limber the cannon and move them down from the hilltop. But the women who had been out that morning had wakened their families, and Louise Michel, the so-called “Red Virgin,” the fighter for socialism, had donned her National Guard uniform and run out to assist. The crowd threw bottles and rocks at the regular soldiers. One observer saw “women and children swarming up the hillside in a compact mass; the artillerymen tried in vain to fight their way through the crowd, but the waves of people engulfed everything, surging over the cannon-mounts, over the ammunition wagons, under the wheels, under the horses’ feet, paralyzing the advance of the riders who spurred on their mounts in vain. The horses reared and lunged forward, their sudden movement clearing the crowd, but the space was filled at once by a backwash created by the surging multitude.” A national guardsman shouted, “Cut the traces!” Men and women drew their knives and cut the harnesses that tied the cannon to the horses. To cries of encouragement, the artillerymen left the guns and joined the crowd in eating meat, rolls, and wine. On the other side of the hill, troops refused to fire on a national guard platoon. The national guard began building a barricade. The troops withdrew.

On Montmartre itself, General Lecomte stepped forward to get the guns moving again. He ordered his men to fire into the crowds. They did not move. He ordered again, and still the men did not fire. He ordered a third time. A woman shouted back, “Will you fire on us? On your brothers? On our husbands? On our children?” Lecomte threatened to shoot any man who refused to fire and asked if his men “were going to surrender to that scum?” Louise Michel later wrote that a noncommissioned officer left ranks, “placed himself before his company and yelled, louder than Lecomte, ‘Turn up your rifle butts!’ The soldiers obeyed… [T]he Revolution was made.”

All of the columns were engaged in similar scenes, though the troops on rue Lepic had been beaten off by gunfire. National guardsmen took Lecomte and a few other officers prisoner.

Mayor Clemenceau, a petit-bourgeois politician and mayor of the 18th Arrondissement, which contained Montmartre, went down to broker the general’s release. At the same time, national guardsmen arrived with another prisoner: General Clément Thomas, the butcher of ‘48, who had slaughtered so many working people during the June Days. The crowd pulled Thomas and Lecomte into a garden and shot them both.

Adolphe Thiers ordered the troops out of the city to regroup at Versailles and ordered the evacuation from the forts of Mont-Valérien, Issy, Vanves, and Montrouge. He quickly realized that abandoning Mont-Valérien was a mistake, and his troops beat off a halfhearted assault by the National Guard to retake it.

The communist Rigault took command of the police. He ordered the release of political prisoners. The Blanquists demanded the National Guard follow Thiers’ retreating army to Versailles and destroy the Versailles government, but the Central Committee of the National Guard (which had been reorganized along democratic lines) demurred. The Jacobins and members of the International agreed; they would try to resolve the crisis by peace.

On 19 March, Émile Duval warned the Central Committee that conservative elements in the wealthy First and Second Arrondissements were on the move. They had summoned their conservative, bourgeois National Guard units to Versailles. Members of the committee protested that they did not have the popular mandate to defend Paris and refused to take authority over the revolution. They only went so far as to order detachments of guardsmen to key points in the city such as the Bank of Paris and the Tuileries. The committee then determined to hold elections.

They sent out a list of demands to the National Assembly in Versailles insisting that Paris be granted the right to elect its own mayors, that the prefecture of police be abolished, that the regular army be kept outside of Paris, that the National Guard be allowed to elect its officers, that the moratorium on rents be resumed, and that the National Assembly proclaim the republic. They declared that since 18 March, Paris “has no other government than that of the people and this is the best one. Paris is free. Centralized authority no longer exists.” But the mayors of the arrondissements refused to meet with the central committee, as did the deputies of Paris in the National Assembly.

The conservative and monarchist National Assembly met in a secret session on 22 March. They determined that no concessions would be made. “The criminals who now dominate Paris have attacked Paris: now they attack society itself.” Thiers explained that they should give the Commune time to establish itself while they built up an army so they could make the bloody execution of the Commune’s members appear legitimate. Thiers relished the thought of civil war. It was understood by Thiers and others in the Assembly that this was a class war.

On March 23, the Paris branch of the International proclaimed, “The independence of the Commune will mean a freely discussed contract which will put an end to class conflict and bring about social equality.” The supporters of the Commune were now being called Communards, and the specter of Communism clearly animated the Versailles government, which was terrified that the Commune would redivide property. Protestant minister Élie Reclus said, “Lazare, always starving, is no longer content with the crumbs that fall from the table of the rich, and now he has dared ask for his part of the feast.”

The city held municipal elections on 26 March to elect a central council of the Commune. Most of the delegates were Jacobins, Blanquists, and members of the International — the wealthiest residents had already fled the city.

The Commune needed money. It needed to pay the national guardsmen their 1.50 francs a day and to pay its municipal employees their workman’s wage. Arguments broke out in the provisional authority over where the money was to be gotten. Some demanded the remaining gold reserves left during the siege be taken from the Bank of France. However, the delegate for finance, François Jourde, instead arranged a loan of 700,000 francs and credit for 16 million francs more — nothing compared to the 258-million-franc credit received by Versailles.

The Commune Council met 57 times during the life of the Commune. It established executive commissions, each run by a delegate. These commissions convened twice daily at the Hôtel de Ville, but the meetings ran long, were increasingly contentious, and wasted much time discussing issues of no importance. Some members were swept away in the ceremony of their new authority. Most of the servants of the Commune had no experience in government.

On 10 May, the newly constituted German Empire and Thiers’ treasonous Versailles government signed the Treaty of Frankfurt, formalizing the capitulation of France. Immediately, Bismarck released captured French soldiers to Versailles, swelling the size of the counterrevolutionary army.

The forces of the Commune were led by their delegate for war, Gustave Cluseret, a Paris-born graduate of the elite military school of St. Cyr. He had been wounded in Algeria in the colonial venture of the very last Bourbon king and had fought as a commander of the Guarde Mobile to put down the June Days in 1848. He had gone to the United States to fight for the Union Army in the American Civil War and become an American citizen. He returned to France in 1867 committed firmly to social revolution and was jailed in 1868 for writing revolutionary articles.

He believed that if he could hold off Thiers and his minions, the Commune would be able to reach a negotiated settlement with Versailles. But the National Guard resisted Cluseret’s attempts to make it into a regular army. The democratic councils within the Guard sent out their own commands and ignored Cluseret.

The first fighting began on March 30, 1871, two days after the Commune was officially proclaimed. A patrol of the Versailles army came upon a Communard perimeter post. The troops hesitated to fire. General Gaston Gallifet ordered the artillery to fire and threatened them with a pistol. He then charged forward and took prisoners as the Communards fled. This was the first time the army had obeyed orders to attack their fellow Parisians and Frenchmen. It would not be the last.

On April 2, a skirmish broke out at Courbevoie. A military surgeon general called Pasquier approached the Communard lines to negotiate, but his uniform resembled that of a gendarme colonel. The Communards shot him, and a firefight saw the Communards beaten. Thirty or so Communards were taken prisoner, but General Vinoy ordered that all soldiers, men from the Guarde Mobile, and sailors who were taken prisoner were to be shot. There would be no quarter and no prisoners. Any citizens of Paris taken under arms would be summarily executed as traitors.

In response to the losses at Courbevoie and the massacre of the Communards there, the Commune assembled some 20,000 men and, in the early morning of 3 April, they marched out of Paris towards Versailles. The cannons of the national government began to shell them immediately from Mont-Valérien. The columns straggled. They failed to coordinate. Some of the National Guard seemed to be barely paying attention as the troops from Versailles closed on their positions.

In fact, many of the guardsmen assumed that the line troops would not fire on them and would turn their rifles around, butt up, like they had done on Montmartre. They did not. Two Communard generals, Émile Duval and Gustave Flourens, important and energetic men within the Commune, were taken captive. Flourens was hacked to death on the banks of the Seine by a gendarme. Duval and his chief of staff were shot.

This disorganization and hesitance would typify every military action taken by the Commune. By the time it was determined to act, it was already too late.

The Red Flag

The Commune banned the death penalty, though Thiers had no such scruples. On April 7 at the place Voltaire, below the prison of La Roquette, the national guardsmen burned a symbolic guillotine.

On April 16 the Commune ordered a survey of abandoned workshops. They expropriated these and turned them into workers’ cooperatives. A cooperative iron foundry was started in Grenelle employing 250 workers and producing shells for the city’s defense. Night baking was abolished on 20 April. Maximum salaries for municipal employees were set at 6,000 francs a year. Employers were barred from assessing fines from workers’ wages. Labor exchanges were established.

“The social revolution will not be operative until women are equal to men. Until then, you have only the appearance of revolution,” proclaimed Citoyenne Destrée. Louise Michel said, “[A woman] bends under mortification; in her home her burdens crush her. Man wants to keep her that way, to be sure that she will never encroach upon his function or his titles. Gentlemen, we do not want either your functions or your titles.” Proletarian women were (and are) doubly exploited — by gendered labor and by their employers. Bosses are the “social wound that must be taken care of.”

Élisabeth Dmitrieff, née Elisavieta Koucheleva, was actually dispatched to the Commune by Marx himself to act as an observer there. She became intimately involved in calling for the creation of workshops for unemployed women, for equal salaries for male and female workers, and for a reduction in overall work hours within the Commune. She founded the Union des Femmes alongside four other women and took a position as its general secretary.

The Commune held up a revolutionary morality — a high standard of honesty and accountability. The Commune rejected high salaries for officials. Public servants in appearance and rhetoric were to be public servants in fact. Marx covered the public aspects of the Commune and its political organization in detail.

The Commune was formed of the municipal councillors, chosen by universal suffrage in the various wards of the town, responsible and revocable at any time. The majority of its members were naturally working men, or acknowledged representatives of the working class…. The police, which until then had been the instrument of the Government, was at once stripped of its political attributes, and turned into the responsible, and at all times revocable, agent of the Commune. So were the officials of all other branches of the administration. From the members of the Commune downwards, the public service had to be done at workmen’s wages. The privileges and the representation allowances of the high dignitaries of state disappeared along with the high dignitaries themselves…. Having once got rid of the standing army and the police, the instruments of physical force of the old government, the Commune proceeded at once to break the instrument of spiritual suppression, the power of the priests…. The judicial functionaries lost that sham independence… they were thenceforward to be elective, responsible, and revocable.

Karl Marx, The Civil War in France, pp. 217-21 (1973)

To illuminate what this meant, Lenin compared the governance of the Commune to the modern parliamentary “democracies.” The bankrupt nature of “representative” government in, for instance, the U.S. Empire is made clear by the comparison to the truly representative government of the Commune.

The way out of parliamentarism is not, of course, the abolition of representative institutions and the elective principle, but the conversion of the representative institutions from talking shops into “working” bodies…. [T]his is a blow straight from the shoulder at the present-day parliamentarian country, from America to Switzerland, from France to Britain, Norway and so forth — in these countries the real business of “state” is performed behind the scenes and is carried on by the departments, chancelleries, and General Staffs. Parliament is given up to talk for the special purpose of fooling the “common people.”

V.I. Lenin, The State and Revolution (1918)

Counterrevolution: The Bloody Week

On April 2, the second siege of Paris began; Versaille ordered the armies of counterrevolution to begin shelling Paris. By 21 May, Versailles had indiscriminately killed hundreds and possibly thousands of Parisians and destroyed hundreds of buildings in the western and central districts. The British resident John Leighton said that Versailles was “not content with” battering forts and ramparts killing Communard soldiers but also targeted “women and children, ordinary passers-by [including] unfortunates who were necessarily obliged to venture into the neighbouring streets, for the purpose of buying bread.” U.S. diplomat Wickham Hoffman agreed: “It must always be a mystery why the French bombarded so persistently the quarter of the Arch de Triomphe — the West End of Paris — the quarter where nine out of ten of the inhabitants were known friends of the Government.”

This was worse by far than the Prussian siege. Versailles bombed medical facilities. Thiers proclaimed defense of property while the cannons of Versailles obliterated rows of houses on the Champs-Élysées.

The Commune tried to achieve a negotiated settlement with Versailles, but every attempt was rebuffed. Even as late as 21 April, the Freemasons in the city sent a delegation, but Thiers sent them away with the dismissive (and telling) remark that “A few buildings will be damaged, a few people killed, but the law will prevail.”

On April 28, with the Versailles cannon pounding the city continuously and threatening to reduce its fortifications, the Commune floated a plan for a five-member Committee of Public Safety. On May 1, the Commune approved the creation of the committee by a vote of 34-28. The Committee was a self-conscious echo of the 1793 Committee of Public Safety. It immediately called up General Gustave Cluseret, and, blaming him for transforming the National Guard into an effective army, he was accused of treason and incarcerated in the Conciergerie.

One by one, the forts of Paris fell to the army of Versailles. The National Guard showed up in fewer and fewer numbers to their musters. On May 9, only 7,000 guardsmen arrived to a call that was meant to call up 12,000. On May 12, Jenny Marx, who was in Paris, told her father that the Paris Commune would be destroyed. “We are on the verge of a second June massacre.”

Spies and counterrevolutionaries in the employ of Thiers brought him information about the state of affairs in the city. He spoke menacingly of his obligation to order “dreadful measures” to destroy the Communards. He bribed guardsmen away and operated a secretive military organization within the walls.

On May 15, the leaders of the Commune saw that the end was coming. They knew they could not defend the city. Instead, the Commune determined to deny the old order of the city, to destroy the symbols of despotism and class-rule throughout the city. They fired Adolphe Thiers’ house first. They destroyed the Vendôme Column, the symbol of Napoléon’s empire, on May 16.

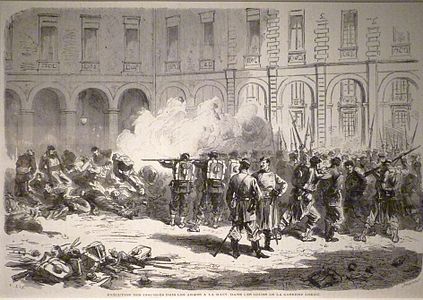

On May 21, a counterrevolutionary in the city realized the Point-du-Jour was undefended and Porte Saint-Cloud was unmanned. He waved a white flag from the ramparts and Thiers’ killers entered the city. Within the hour, line troops under General Félix Douay had entered the capital. Porte Saint-Cloud and Porte d’Auteuil fell without resistance. The defenders began to build their last barricades within the city, each National Guard unit taking responsibility for its own defense and refusing to follow central orders.

Versailles moved slowly, executing everyone under arms they found. They swept the streets for traps, mines, and ambuscades. They poured fire into any house they believed held Communards. Fifty thousand line troops were soon in Paris and, within seventeen hours, 130,000 of Versailles soldiers, along with heavy artillery, had entered the city. They moved easily along the great boulevards. No Communard cannons concentrated on them — they were too uncoordinated. In twenty-four hours, Versailles had taken one-third of Paris from the Commune. Everyone they captured, they gunned down.

A woman ran into a building carrying a red flag. She was found in her attic with crates of weapons. The troops of Versailles hauled her down the stairs, but shot her before they reached the bottom.

The barricades were not enough. That Monday, on the rue Montmartre, a retreating Communard soldier screamed in tears, “Betrayed! Betrayed! They came in where we did not expect them!” At the place d’Italie, national guardsmen secretly tossed away their rifles, muttering, “It is the end!”

Vainly, at this late hour, the Commune proclaimed the levée en masse, the universal armament of the inhabitants of Paris. The American, W. Pembroke Fetridge, watched about thirty women demand a mitrailleuse machine gun to protect their barricade defending the Place du Palais-Royal. “They all wore a band of crepe round the left arm; each one had lost a husband, a lover, a son, or a brother whom she had sworn to avenge. Horses being at this time scarce in the service of the Commune, they harnessed themselves and dragged [the mitrailleuse] off, fastening their skirts round their waists lest they should prove an impediment to their march. Others followed, bearing the caissons filled with munitions. The last carried the flag.”

On Tuesday, the Commune issued an order stating, “Blow up or set fire to the houses which may interfere with your system of defense. The barricades should not be liable to attack from the houses.” The Commune ordered the burning of any house from which Versailles fired shots.

The Palace of the Conseil d’État was burned to deny it to the enemy. The Committee of Public Safety ordered the destruction of the Palais-Royal. The Ministry of Finance was torched. The Naval Ministry went up; the Hôtel de Ville was ordered destroyed. The Commune had become the scene of intense despair. Better to burn down the city than to give it to the enemy. Louise Michel warned, “Paris will be ours or cease to exist.” On Tuesday, May 22, the Communard general Jean Bergeret ordered the Tuileries Palace to be consigned to the fire. Two days later, a Montmartre woman asked what was burning; the Communard replied, “It’s nothing at all,” only the Palais-Royal and the Tuileries, “because we do not want a king any more.”

Communards were executed regardless of their resistance now. On the rue Saint-Honoré, line troops found thirty national guardsmen in a printing shop with no weapons. They took them to the rue Saint-Florentin and shot them in the enormous ditch in front of the remains of the barricade. Nearby, on the rue Royal, troops found six men and a young woman hiding in barrels. They were thrown in a ditch and killed. When line troops reached the place, Vendôme, Versailles shot thirty Communards.

At the Church of the Madeleine, Versailles used a mitrailleuse to execute 300 Communards. On May 23, an officer ordered a soldier who refused to shoot women and children shot. Not far away from there, troops killed a man who had done nothing, then shot his wife and child when they hugged him too long and then shot a passing doctor who tried to help the child.

By Friday, the line soldiers were lying to national guards on the barricades, telling them to come down and all would be well. They were taken aside and shot. Victims were taken to basements or attics to be executed. Police detachments hunted for suspected Communards. On Saturday evening, the Versailles troops blew up the gates at Père Lachaise and stormed in. Hundreds of Communards fell in the rows in hand-to-hand bayonet combat amid the tombs. Hundreds of guardsmen were lined up in rows along a wall and machine-gunned. Clemenceau would later recall that the machine guns were firing for thirty minutes without pause. On Sunday, groups of 150, 200, and even 300 were brought continuously to the cemetery where they were machine-gunned by the troops of Adolphe Thiers.

Pierre Vésinier, a journalist and member of the Commune, wrote that thousands of bodies “strewed the avenues and tombs. Many were murdered in the graves where they had sought shelter, and dyed the coffins with their blood…. [T]errible fusillades, frightful platoon fires, intermingled with the crackling noise of mitrailleuses, plainly told of the wholesale massacre…. Property, religion, and society were once more saved.”

Sunday, May 28, 1871, marked the end of the Commune. Executions continued until the end of July.

Lessons from the Paris Commune

“Why do the anti-authoritarians not confine themselves to crying out against political authority, the state? All Socialists are agreed that the political state, and with it political authority, will disappear as a result of the coming social revolution, that is, that public functions will lose their political character and will be transformed into the simple administrative functions of watching over the true interests of society. But the anti-authoritarians demand that the political state be abolished at one stroke, even before the social conditions that gave birth to it have been destroyed. They demand that the first act of the social revolution shall be the abolition of authority. Have these gentlemen ever seen a revolution? A revolution is certainly the most authoritarian thing there is; it is the act whereby one part of the population imposes its will upon the other part by means of rifles, bayonets and cannon — authoritarian means, if such there be at all; and if the victorious party does not want to have fought in vain, it must maintain this rule by means of the terror which its arms inspire in the reactionists. Would the Paris Commune have lasted a single day if it had not made use of this authority of the armed people against the bourgeois? Should we not, on the contrary, reproach it for not having used it freely enough?”

(emphasis added.) Friedrich Engels, On Authority (1874)

“[T]wo mistakes destroyed the fruits of the splendid victory. The proletariat stopped half-way: instead of setting about “expropriating the expropriators,” it allowed itself to be led astray by dreams of establishing a higher justice in the country united by a common national task; such institutions as the banks, for example, were not taken over, and Proudhonist theories about a “just exchange,” etc., still prevailed among the socialists. The second mistake was excessive magnanimity on the part of the proletariat: instead of destroying its enemies it sought to exert moral influence on them; it underestimated the significance of direct military operations in civil war, and instead of launching a resolute offensive against Versailles that would have crowned its victory in Paris, it tarried and gave the Versailles government time to gather the dark forces and prepare for the blood-soaked week of May.

But despite all its mistakes the Commune was a superb example of the great proletarian movement of the nineteenth century…. The Commune taught the European proletariat to pose concretely the tasks of the socialist revolution.

The lesson learnt by the proletariat will not be forgotten.”

V.I. Lenin, Lessons of the Commune (1908)

The Commune has taught us the form and has played a historical role as the forerunner to the new society yet to come. It has taught us, too, that we cannot be lax in the prosecution of the social revolution. We cannot forget what our enemies will do to us if they should get the chance. Behind every smiling politician lurks the face of Adolphe Thiers, and behind every executive order is the Party of Order, waiting to strangle the revolution in its infancy.

Men and women died to teach us these lessons; they have died so that the revolution, the same revolution, their revolution and ours, may live.